2 are derived assuming a 0.48 R ⊙ host star ( 19). Disparate star properties have been reported in the literature for Kepler-235.

Kepler-235e and Kepler-296 e and f are verified planets ( 39) with uncertain properties. These are represented by the artist’s conceptions, also scaled in size with respect to the Earth. Five of the Kepler HZ discoveries are planets that have been statistically validated at the 99% confidence level or higher: Kepler-22b ( 35), Kepler-61b ( 36), Kepler-62 e and f ( 37), and Kepler-186f ( 38), with radii of 2.38 ± 0.13, 2.15 ± 0.13, 1.61 ± 0.05, 1.41 ± 0.07, and 1.11 ± 0.14 R ⊕, respectively. The symbols are sized in proportion to the Earth image to reflect their relative radii. 2, where the y axis is the effective temperature of the host star.įrom the first 3 y of data (Q1–Q12), there are over 100 candidates that have an insolation flux that falls within the optimistic HZ.

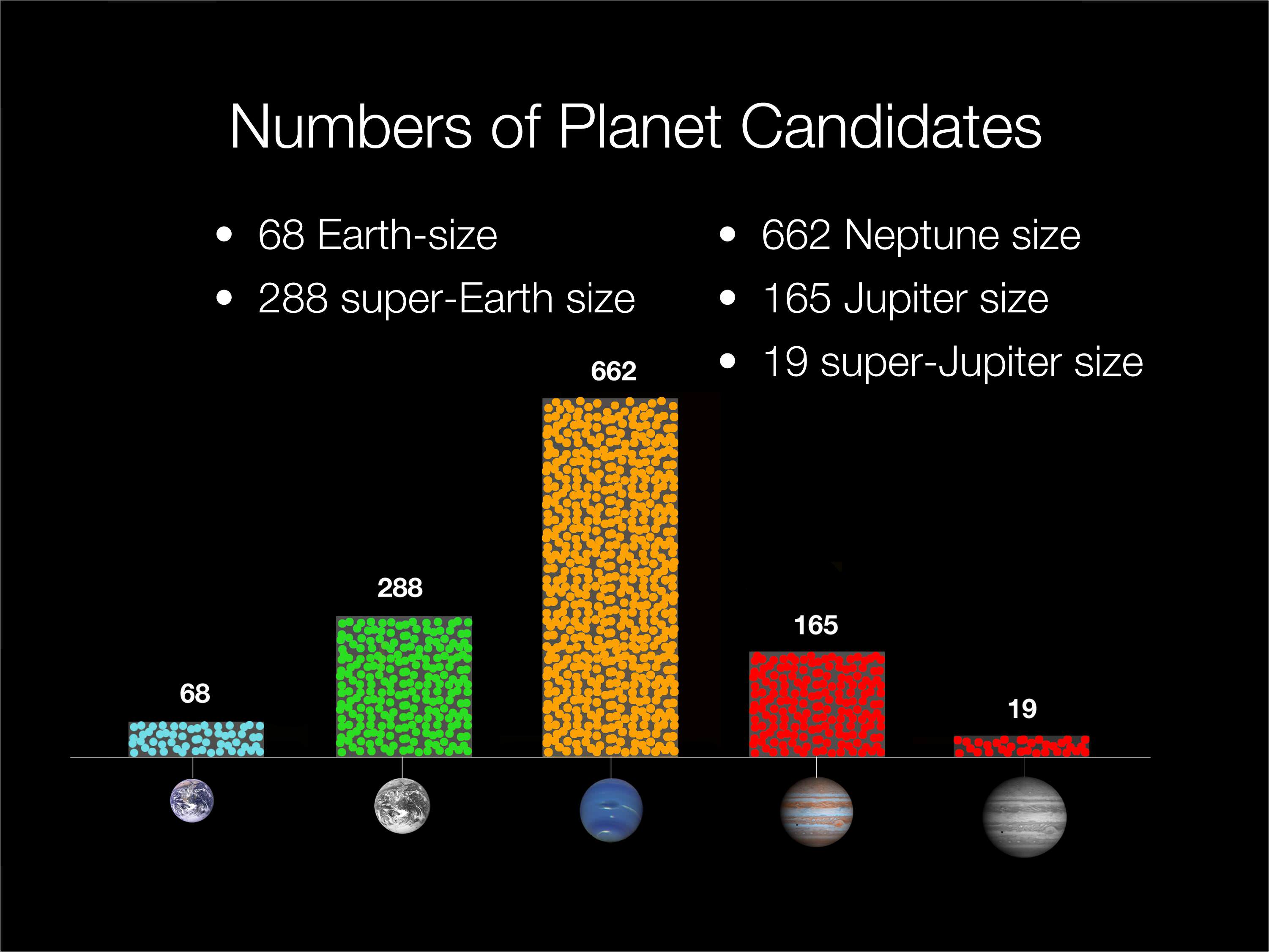

The insolation flux of each planet candidate is shown in Fig. The orbital environment can also be characterized by the irradiation, or insolation flux, defined as F = ( R ∗ / R ⊙ ) 2 ( T ∗ / T ⊙ ) 4 ( a ⊕ / a p ) 2. For Kepler’s exoplanets, comparisons with Earth are made considering size (radius) and orbital environment (period or semimajor axis), both of which require knowledge of the host star properties. Regardless, it is of interest to understand the prevalence of planets with properties similar to Earth. There may not be a simple evolutionary pathway that lands an exoplanet inside of a well-defined HZ. And Lissauer ( 33) considers the dessication of planetary bodies before their M-type host stars settle onto the main sequence. ( 30) consider the extreme case of arid Dune-like planets. As we broaden our perspective, we stretch and prod the HZ limits. Defined as the region where a rocky planet can maintain surface liquid water, the HZ is a useful starting point for identifying exoplanets that may have an atmospheric chemistry affected by carbon-based life ( 28). Kepler’s objective is to determine the frequency of Earth-size planets in the HZ of Sun-like stars. Here, I report on the progress Kepler has made measuring the prevalence of exoplanets orbiting within one astronomical unit of their host stars in support of the National Aeronautics and Space Administration’s long-term goal of finding habitable environments beyond the solar system. Population studies suggest that planets abound in our galaxy and that small planets are particularly frequent. Dynamical (e.g., velocimetry and transit timing) and statistical methods have confirmed and characterized hundreds of planets over a large range of sizes and compositions for both single- and multiple-star systems. The catalog has a high reliability rate (85–90% averaged over the period/radius plane), which is improving as follow-up observations continue. Over 3,500 transiting exoplanets have been identified from the analysis of the first 3 y of data, 100 planets of which are in the habitable zone. The mission has made significant progress toward achieving that goal. Its legacy will be a catalog of discoveries sufficient for computing planet occurrence rates as a function of size, orbital period, star type, and insolation flux. The Kepler Mission is exploring the diversity of planets and planetary systems.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)